Confession: I’m a grammar nerd (some have even called me a grammar ‘nazi’). So in the matter of when to use ‘which’ or ‘that’, I’d like to offer some helpful guidelines.

“Whether or not to use ‘that’ as a relative pronoun must be one of the most fraught questions in any sensitive writer’s mind.” — Philip Hensher @PhilipHensher

British vs U.S. Views: Philip Hensher, a British author, wrote an article for LitHub that attempts to sort out the conundrum … from the British perspective.

The Brits have been using ‘which’ for centuries in certain cases where we in the U.S. currently prefer ‘that’. Hensher provides an example of British writers saying “She gave me the book which I wanted,” and notes that Americans would prefer using ‘that’ instead of ‘which’ in this example. Although many documents from early in U.S. history – influenced by our British founders – reflect such use of ‘which’, current preferences have changed.

Hensher attempted to explain the difference in terms of whether the words following these pronouns are “necessary to the meaning” of the preceding part of the sentence (in which case use ‘that’), versus not “fundamentally affect[ing] the meaning or the structure of the first” part of the sentence (so use ‘which’).

Well, that can often be an unclear distinction, subject to differing views, even for Hensher himself.

Let’s explore and expand upon the distinction, with some guidelines to help you decide when to use each of these pronouns. Although they’re a little more specific than Hensher’s model, they are nevertheless ‘guidelines’, not ‘rules’. I emphasize this because I do agree with him that sometimes overly strict adherence to grammatical correctness can stifle ‘expressive choice’ and style.

Chicago Style makes the distinction similar to Hensher’s, and adds the terms Restrictive vs Nonrestrictive clauses:

A relative clause is considered ‘restrictive’ if it provides information essential to the meaning of the sentence. Like dependent or subordinate clauses (of which they are a subset), restrictive relative clauses [a.] will include a subject and verb, [b.] do not make sense standing alone, [c.] are introduced by a relative pronoun e.g. ‘that’ (or who/whom/whose), and [d.] are not set off by commas from the rest of the sentence. The pronoun ‘that’ may occasionally be omitted (but needn’t be) if the sentence is just as clear without it, as in the second example below. The relative pronoun may sometimes serve as the subject in the clause, as in the third example below.

- The version of the manuscript that the editors submitted to the publisher was well formatted.

- The book [that] I have just finished is due back tomorrow; the others can wait.

- I prefer to share the road with drivers who focus on the road rather than on what they happen to be reading.

By contrast, a relative clause is considered ‘nonrestrictive’ (subset of independent clause) if it can make sense standing alone — i.e. the clause can be omitted without affecting the word it refers to or otherwise changing the meaning of the rest of the sentence. Nonrestrictive relative clauses are often seen as an aside, an afterthought. Although they include subject and verb and are introduced by a relative pronoun (‘which’ [or who/whom/whose]), they are set off from the rest of the sentence by commas.

- The final manuscript, which was well formatted, was submitted to the publisher on time.

- Ulysses, which I finished early this morning, is due back on June 16.

- I prefer to share the road with illiterate drivers, who are unlikely to read books while driving.

Chicago Style notes that although ‘which’ may sometimes be substituted for ‘that’ in a restrictive clause, such practice is common in British English, while most present-day U.S. writers maintain the distinction between restrictive ‘that’ (with no commas) and nonrestrictive ‘which’ (with commas).

Chicago Style further explains:

- In polished American prose, ‘that’ is used restrictively to narrow a category or identify a particular item being talked about.

[“Any building that is taller than three stories must be outside the area.”] - On the other hand, ‘which’ is used nonrestrictively—not to narrow a class or identify a particular item but to add something about an item (or action) already identified. [“Beside the officer trotted a toy poodle, which is hardly a typical police dog.”]

[“The silence was broken by a shout, which signaled the start of the race.”] - ‘Which’ can be used restrictively only when it is preceded by a preposition.

[“The situation in which we find ourselves is untenable.”]

Otherwise, it is almost always preceded by a comma, a parenthesis, or a dash. - In British English, writers and editors seldom observe the distinction between ‘that’ and ‘which’.

Relative clauses can describe or refer to different words in the main sentence. How the clause is used can provide further clues regarding whether it’s restrictive or nonrestrictive.

- When a relative clause refers to a noun in the foregoing part of a sentence, it is an adjectival clause.

- If the clause describes the noun, is essential to the noun’s identity and cannot make sense standing alone, it is a restrictive relative clause. Therefore: Use NO comma + ‘that’.

“Any building that is taller than three stories must be outside the area.” (‘taller than three stories’ qualifies the building, thereby functioning as an adjective)

In many cases – increasingly preferred in contemporary U.S. usage — ‘that’ can be omitted (and thus it’s implied): “Any building taller than three stories must be outside the area.”

- If the clause describes the noun, is essential to the noun’s identity and cannot make sense standing alone, it is a restrictive relative clause. Therefore: Use NO comma + ‘that’.

- When a relative clause can stand alone, it is a nonrestrictive clause and the relative pronoun introducing it typically (though not always) serves as Subject with the verb. Therefore: Use comma + ‘which’.

Depending on what that clause is referring to – noun or verb – the clause serves as either:- Adjective: “Beside the officer trotted a toy poodle, which is hardly a typical police dog.”

In this case the clause comments on the dog and thus serves as a nonrestrictive adjectival clause. - Adverb: “Then he shouted, which is what he always did to start the race.”

In this case, the clause comments on the shouting, thus serving as adverbial clause.

- Adjective: “Beside the officer trotted a toy poodle, which is hardly a typical police dog.”

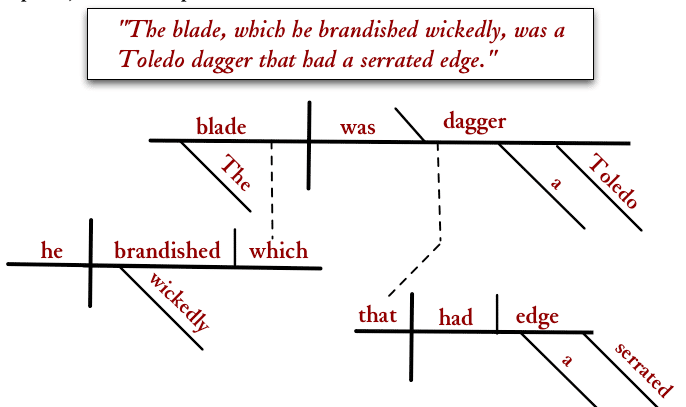

Granted, the use of relative pronouns can be tricky. If you are of the generation that cut their teeth on diagramming sentences, this is probably a cake walk for you. But the fun (I mean it!) of the lost art that broke down & visualized sentence elements and their relationship to each other has been eliminated from schools.

So – stay with me here – let’s consider “The silence was broken by a shout, which signaled the start of the race.”

- In this sentence, the nonrestrictive clause might be referring to the act of breaking the silence – in which case it would be an adverbial clause (i.e., it is the breaking of silence that is the signal).

- Or you could intend “which signaled the start of the race” to refer to the noun “shout” so it would be an adjectival clause.

- If the latter is so, ‘that’ could take the place of ‘which’ (without the comma):

“The silence was broken by a shout that signaled the start of the race” – but only IF the writer intends “signaled the start of the race” to be an attribute of that particular ‘shout’ (different from some other shout that wouldn’t have the same effect). - And finally, for the “drop the ‘that’” preference to work, you’d need to modify to “The silence was broken by a shout signaling the start of the race.”

How you structure your sentences makes a difference to meaning.

I know I said these are only guidelines, not hard & fast rules, but Here’s one “rule” (sorry), which directly contradicts Hensher’s example of British usage (“She gave me the book which I wanted”):

When used as a relative pronoun introducing a clause,

‘which’ must always be preceded by a comma. If not, use ‘that’.